[Some computers might ask you to allow the music to play on this page]

Dexter Gordon by Robin Kidson

|

Jazz developed a certain image from the 1940s onwards as a music for rebels played by cool and stylish people who lived outside the conventions of bourgeois society. They drank and smoked and took drugs; they lived hard and sometimes died romantically young but never gave a damn. The place in which that image was forged was the night club, the smoky, boozy,  slightly raffish space in which smoky, boozy and slightly raffish musicians could ply their trade and develop their art. It was the market place where sellers met buyers who wanted to let their hair down and exercise some sense of ersatz rebellion against convention even if they had to return to the workplace on Monday morning.

slightly raffish space in which smoky, boozy and slightly raffish musicians could ply their trade and develop their art. It was the market place where sellers met buyers who wanted to let their hair down and exercise some sense of ersatz rebellion against convention even if they had to return to the workplace on Monday morning.

Many jazz clubs have become legendary and have passed into the popular consciousness: Birdland, the Cotton Club, the Village Vanguard, Ronnie Scott's…. The Café Montmartre (or the Jazzhus Montmartre to give it its proper Danish name) in Copenhagen may not be as well-known but it is a space in which many of the greatest names in jazz have performed over the years.

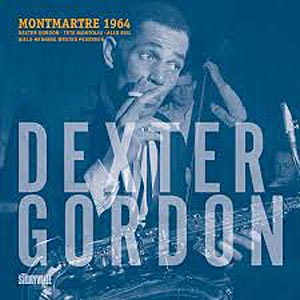

One of those names is Dexter Gordon and Danish record label, Storyville, has recently released a superb live recording of him playing at the Jazzhus Montmartre in 1964. At the time, the Jazzhus was a relatively new club. It first opened in 1959 in Dahlerupsgade. In 1961, it moved to new premises in Store Regnegade where it stayed until 1976. It quickly became a venue not only for local Danish musicians but also for visiting American stars touring Europe.

This grainy old piece of film shows Bud Powell playing Anthropology at the club in 1962. He is joined by Jorn Elniff on drums and a very young Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen (NHØP to his English speaking friends) on bass. NHØP became the club’s house bassist and, rather like Stan Tracey at Ronnie Scott’s, honed his craft playing with the greatest jazz stars of the day until he became one of those stars himself. The film also has glimpses of a physical feature of the club – a series of plaster masks created by artist Mogens Gylling that hung on the walls. The film may be a bit shaky but captures what the club must have been like in those days: packed, smoky, and boozy with great music to boot.

In 1976, the club moved again to Nørregade 41. It continued to host the biggest names of the day including the likes of Miles Davis, Stan Getz, Sonny Rollins, Oscar Peterson…. In fact, it might be easier to list the stars who didn’t play at the Jazzhus Montmartre. The club also featured rock and soul music, and held a popular and profitable disco at the weekends which, to some extent, subsidised the less commercial jazz activities. For a sense of what the club might have been like in this phase of its existence, here is Stan Getz playing I Thought About You live at the Montmartre in 1987.

Stan Getz had a long association with the Jazzhus, playing the club many times throughout his career and recording live albums there. Indeed, he actually resided in Copenhagen in the late fifties/early sixties, part of an extraordinary expat community of top American jazz musicians who opted to live in Denmark in the sixties and the seventies.

In addition to Getz, their number included Ben Webster, Oscar Pettiford, Benny Carter,

Kenny Clarke, Kenny Drew, Thad Jones and many more. One of the attractions of Copenhagen for black musicians was the lack of discrimination compared to the United States. There was a more relaxed and liberal lifestyle in the city which attracted black and white alike; and a greater respect for jazz  and jazz musicians. To some extent, the expats could also throw off the bad boy image of jazz which for some had become a millstone. Stan Getz, for example, wanted to escape the drug culture that had enveloped him and led to spells in jail.

and jazz musicians. To some extent, the expats could also throw off the bad boy image of jazz which for some had become a millstone. Stan Getz, for example, wanted to escape the drug culture that had enveloped him and led to spells in jail.

The expats contributed to a thriving jazz scene in Copenhagen much of which was centred around the Jazzhus Montmartre. One of the expats, Kenny Drew, became the club’s house pianist joining NHØP on bass and Alex Riel on drums. Other Danish musicians played with both expats and touring stars, learning from them and then developing their own styles and becoming, like NHØP, internationally recognised artists in their own right. Palle Mikkelborg, for instance, creator of Miles Davis’ last great work, Aura, cut his teeth at the Jazzhus as did Bo Stief and Jesper Lundgaard.

In the early 1990s, the Jazzhus Montmartre went through various changes in ownership and it moved further and further away from its jazz focus. It closed altogether in 1995. However, in 2010, entrepreneur Rune Bech and pianist Niels Lan Doky got together and reopened the Jazzhus back at Store Regnegade – and it is still there although closed at present because of Covid 19 restrictions.

Unlike its previous existences, the club is not a commercial concern and has been set up as a charity with some public funding. It is mainly run by a mixture of part time staff and volunteers. A capacity of 85 ensures it retains its small club ambience and it is still a venue for some of the top jazz talent around as well as being something of a tourist attraction. The original iconic plaster masks disappeared at some point in the club’s chequered history but Mogens Gylling has created a new set.

A glimpse of the club’s current incarnation can be seen in this barnstorming version of Take Five by Danish pianist, Carsten Dahl and his trio recorded live at the Jazzhus in July 2014:

Subject to the lifting of Covid restrictions, the Jazzhus plans to reopen in February 2021. Its website is here and contains much more English language information about the club.

Saxophonist Dexter Gordon first played at the Jazzhus Montmartre in 1962 as part of a European tour. He wasn’t that well known in Denmark but had developed a reputation in the US as a sort of easy listening but skillful bopper. Born in Los Angeles in 1923, he played in various bands in the 1940s before establishing a successful partnership with Wardell Gray. He became the embodiment of  that Bohemian cool image of jazz with all the essential requirements: tall, black and handsome with added charisma and a wardrobe of elegant hip suits. He also had the obligatory drug habit which landed him in prison from time to time. His habitat of choice was the night club and he took to the Jazzhus Montmartre like a bird to the sky.

that Bohemian cool image of jazz with all the essential requirements: tall, black and handsome with added charisma and a wardrobe of elegant hip suits. He also had the obligatory drug habit which landed him in prison from time to time. His habitat of choice was the night club and he took to the Jazzhus Montmartre like a bird to the sky.

He also took to Copenhagen and lived there from 1963 to 1977, joining the growing expat community and participating fully in the Danish jazz scene. He became something of a fixture at the Jazzhus and recorded several live albums there. The tracks on Storyville’s new release, Montmartre 1964, were recorded live at the club in July 1964 and have not been released before. Gordon plays tenor saxophone and is joined by house band members NHØP on bass and Alex Riel on drums. The pianist is not Kenny Drew, though, but Catalonian, Tete Montoliu.

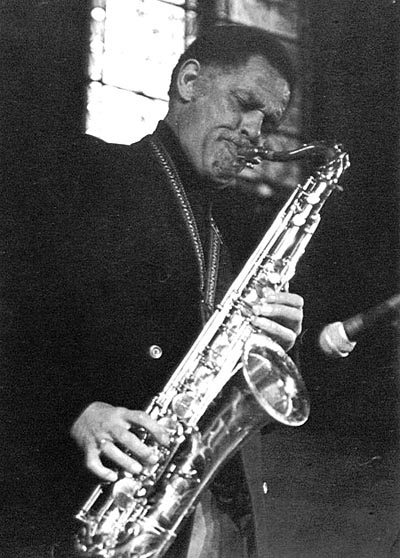

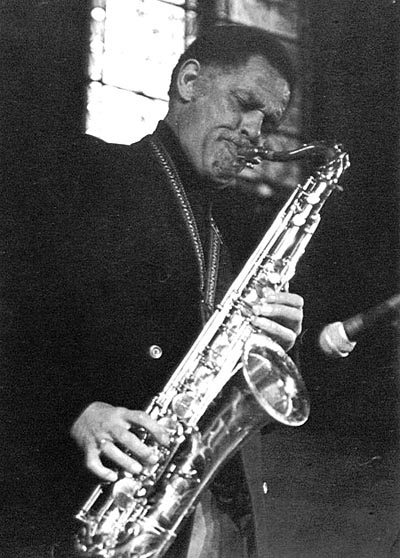

Dexter Gordon c1964. Photograph: Kirten Malone

The first track on Montmartre 1964 is Dexter Gordon’s own composition, King Neptune. For some reason, the track begins halfway through the number just as NHØP begins his solo. The bassist was only 18 at the time but already he is displaying finger blistering brilliance. The CD’s informative liner notes suggest the expat community was already recognising NHØP’s genius, and musicians such as Gordon and Ben Webster were showing him off to visiting American colleagues “like proud grandfathers”. NHØP’s solo is followed by some brief exchanges between Gordon and Riel (shown in this short snatch of film) and then the track ends.

Next up is Big Fat Butterfly on which Gordon sings. He has a pleasant enough jazz voice but one can’t help feeling he should stick to his superb saxophone playing. That playing really hits its stride on the third track, Manha de Carnival, a languid bossa nova by Brazilian composers Luiz Bonfa and Antonio Maria. It helps that the melody is so compelling and memorable. Gordon takes a long solo which, although it sticks pretty close to the tune, is full of imaginative diversions and never strays into cliché. Montoliu’s solo is sparkling and the whole piece is driven along by some brilliant drumming from Riel.

Listen to Manha de Carnival:

The emphasis on improvisation means that much of the art in jazz is in the actual performance, the shining transient moment when the musician applies his or her creativity to the base material to produce wonders. That moment can be captured in the studio but it is in live performance that jazz truly comes into its own. And, for the sort of small group jazz that was the forte of Dexter Gordon, there isn’t much that can beat live performance in the small intimate club. Some of the great jazz albums have been recorded in that sort of environment - Bill Evans at the Village Vanguard, for example, or Ornette Coleman at the Golden Circle. One of the joys of Montmartre 1964 is the way in which the ambience and clientele of the Jazzhus become an integral part of Dexter Gordon’s performance. On an upbeat track like Loose Walk (by Sonny Stitt and Johnny Richards), for example, the claps and yelps from the audience add another dimension and spur the musicians on to ever greater heights and an ever deeper groove. Gordon’s improvisations sound as if he is having a lively conversation with his listeners and NHØP also responds with another scintillating solo.

Throughout Montmartre 1964, Dexter Gordon’s big full confident tone is on display but it is in his improvisations that his genius really shines. Listen how on his own composition I Want More he patiently builds his solo adding layer upon layer of sound, constructing a narrative which draws you in to its twists and turns, its playful wit. His skill is such that an idea in his head is instantly translated into sound. Some of those ideas include snatches of other tunes. The style is reminiscent of Sonny Rollins and it comes as no surprise that Rollins was influenced by Dexter Gordon and not, as one might have expected, the other way round. Here is film of a live performance of I Want More in 1964 - not at the Jazzhus, though, but in Norway:

The penultimate track on the album is a heartfelt rendition of Errol Garner’s ballad, Misty. Again, Gordon manages to stay close to the tune whilst at the same time improvising some elegant embellishments, bringing out the languid melancholy of the original. Listen to Misty:

As well as being a fine performer, Dexter Gordon was also an accomplished composer and Montmartre 1964 includes three of his own pieces including the final track, Cheesecake. It is a strong memorable tune and the musicians give it a good hard bop going over. As with all the other tracks on the album, the quartet runs together like the proverbial well-oiled machine and Gordon gives plenty of space for the others to shine.

Dexter Gordon was good when he came to Denmark but the years of living there and those nights at the Jazzhus made him even better. In 1976, he toured in the US and received such an enthusiastic reception that he was persuaded to return permanently. He became something of an elder statesman and received various accolades and awards. In 1986, he starred in the Bertrand Tavernier film, Round Midnight, which explored that image of the jazzman as existential outsider in the dark interiors of the club. Gordon played a version of himself.

The years of cigarettes, drugs and smoky nightclubs eventually caught up with Dexter Gordon and he died at the relatively young age of 67 in 1990. By that time, the image of the jazzman which he exemplified was coming to an end. Today’s jazz musicians learn their trade in the Conservatoire rather than the club. And the Jazzhus is smoke free. All of which is probably a good thing. Still, it is good to hear albums like Montmartre 1964 to remind us how things used to be, and to hear one of the greats of jazz at the peak of his power.

Click here for more details and samples of Montmartre 1964

Other pages you might find of interest :

© Sandy Brown Jazz 2021

Click HERE to join our mailing list