[Some computers might ask you to allow the music to play on this page]

Remembering Stanley Cowell Blues For The Viet Cong by Robin Kidson

|

Pianist Stanley Cowell, who died at the end of last year, has a special place in my jazz heart. In the late 1960s/early 1970s, I was a student in London. My main extra-curricular activity was jazz. I devoured the jazz pages of the Melody Maker each week, went to as many live gigs that I could, and helped organise jazz events at my college. I kept my ear to the jazz ground, listening out for the latest trends and record releases

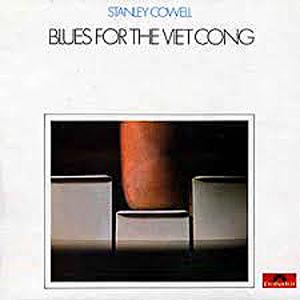

An LP which received a lot of attention around this time was Blues For The Viet Cong by an American pianist called Stanley Cowell. It was released to some fanfare by one of the major mainstream record labels of the day, Polydor, which knew a thing or  two about packaging and PR. For a start, the album had a striking cover – a close up photo of a finger pressing down on a piano key. Also, its title was provocative and therefore newsworthy, as well as appealing to a radical chic sensibility prevalent in those days. And then the more discerning jazz critics said that the music was pretty good too. Intrigued (or, if you prefer, carried away by the hype), I saved up my pennies and bought the album. It joined my very small record collection. The music instantly grabbed me and I played it over and over again. Fifty years on, my record collection has substantially expanded but I still have Blues For The Viet Cong in vinyl - and I still play it.

two about packaging and PR. For a start, the album had a striking cover – a close up photo of a finger pressing down on a piano key. Also, its title was provocative and therefore newsworthy, as well as appealing to a radical chic sensibility prevalent in those days. And then the more discerning jazz critics said that the music was pretty good too. Intrigued (or, if you prefer, carried away by the hype), I saved up my pennies and bought the album. It joined my very small record collection. The music instantly grabbed me and I played it over and over again. Fifty years on, my record collection has substantially expanded but I still have Blues For The Viet Cong in vinyl - and I still play it.

The sleeve notes of my copy of Blues For The Viet Cong say that Stanley Cowell was born in Toledo, Ohio in 1931 but the reference books (and obituaries) put the date ten years later in 1941. He studied classical piano from the age of four but always had an interest in jazz partly stimulated by Art Tatum who was a family friend. His music education was formal, in the classical tradition, and he studied for degrees at Oberlin College and the University of Michigan. His jazz career began to take off in the mid-1960s in New York where he played with Roland Kirk, Marion Brown, Stan Getz and Max Roach.

Blues For The Viet Cong was recorded in London in 1969 and was Stanley Cowell’s first outing as a leader. Cowell plays both piano and electric piano and is joined by fellow Americans, Steve Novosel on bass and Jimmy Hopps on drums. There is nothing in the album’s packaging which explains why Cowell chose the title, Blues For The Viet Cong. The sleeve notes, written by Chris Whent, one of the album’s producers, are a straightforward account of Cowell’s biography and the background to some of the tracks. There is no hint of the kind of sixties radicalism which one assumes Cowell was seeking to represent. Nor is there any indication in the title track of a connection to the Viet Cong. Cowell plays electric piano on the track which is a jaunty, joyful piece of jazz rock with a marvellous main theme and a thumping beat. His improvisations are on the free side creating a futuristic spacey soundscape light years from the jungles of Vietnam. Jimmy Hopps drives the whole piece along with some crisp Tony Williams style drumming. The tune wormed its way into my head back in the 1970s and has never gone away. Even now, in my dotage, I can find myself humming something and wondering, now, where did that come from?. Ah, yes, Blues For the Viet Cong…

All eight tracks on the album are original Stanley Cowell compositions apart from the Rodgers and Hart standard, You Took Advantage Of Me on which Cowell plays solo acoustic piano. He gives the tune a thorough work out in the style of his old mentor, Art Tatum, and with a virtuosity to match. It’s exhausting just listening to it – Chris Whent says in his sleeve notes that, after laying down the track, Cowell’s “only comment, on coming into the booth to hear the tapes, was to ask how long it ran. We told him about four and a half minutes. ‘It felt’, he said, ‘like an hour and a half’”.

Cowell’s Tatum-like virtuosity shines through on all the other tracks. On his own composition, Departure, for example, he takes off on a dazzling improvisation which pulls and pushes the tune in all sorts of different directions. The tune itself is another memorable one, hooking itself effortlessly on to the sub-conscious.

There are more compelling melodies on The Shuttle, which Cowell wrote when flying on the New York-Boston shuttle flight, and on Photon In A Paper World which has another imaginative improvisation with elements of free, blues, jazz rock, even a touch of classical.

Listen to Photon In A Paper World

Most of the compositions are upbeat with a firm pulse but Cowell can also do ballads as on the wistful Wedding March originally written for the bridesmaids at his wedding.

Although the album is definitely Stanley Cowell’s show, he is given sterling support from Steve Novosel and Jimmy Hopps. The latter’s drumming is showcased on Sweet Song, for example. Hopps plays like a demon against Cowell’s gentle piano. The contrast between the two different moods is most effective – it’s as if the singer of the sweet song is burning up inside.

The best is left to last; the final track is the unforgettable Travellin’ Man, another piece of music which has taken up residence in a corner of my brain. Cowell’s intention is described in the sleeve notes: the track “depicts musically an imagined itinerant African musician who limps up to us, plays a simple little tune on what is perhaps a thumb piano and then leaves us as quietly as he arrived. A simple and beautiful little poem”. That description captures perfectly the feel of the piece. Cowell plays electric piano in imitation of that thumb piano; and the rhythm shuffles along like someone limping. It is a complex piece of music which yet conveys simplicity and is a complete success by any measure.

Listen to Travellin' Man

There was, I think, an expectation that Stanley Cowell would go on to have a stellar career with Blues For The Viet Cong acknowledged  as a classic. It didn’t quite happen that way. Cowell recorded another album with Polydor, Brilliant Circles, also in 1969, and, in 1972, released Illusion Suite on ECM but these were his last outings on major labels. He devoted some of his energies in the 1970s to establishing various organisations promoting African-American music including Collective Black Artists Inc. and the record label, Strata-East. This work was often done in collaboration with trumpeter Charles Tolliver with whom he played and recorded as well. He was a member of the Heath Brothers Band from 1974 to 1983 and also played with a range of other artists including J.J. Johnson, Art Pepper, Larry Coryell and Gil Scott-Heron.

as a classic. It didn’t quite happen that way. Cowell recorded another album with Polydor, Brilliant Circles, also in 1969, and, in 1972, released Illusion Suite on ECM but these were his last outings on major labels. He devoted some of his energies in the 1970s to establishing various organisations promoting African-American music including Collective Black Artists Inc. and the record label, Strata-East. This work was often done in collaboration with trumpeter Charles Tolliver with whom he played and recorded as well. He was a member of the Heath Brothers Band from 1974 to 1983 and also played with a range of other artists including J.J. Johnson, Art Pepper, Larry Coryell and Gil Scott-Heron.

Stanley Cowell, Charles Tolliver, Cecil McBee and Jimmy Hopps. Picture from the album Live at Slugs Volume 2

As a leader, Cowell’s own projects included various trios, quartets and the innovative all-piano septet, the Piano Choir. His talents as a composer of both jazz pieces and larger scale classical works were critically acclaimed but did not really receive any wide recognition. An aversion to cigarette smoke led him to reduce live performances in the 1980s and he became increasingly involved in academic work, holding posts at Lehman College, the New England Conservatory and, latterly, at Rutgers University from which he retired in 2013.

Here is a short film which shows him talking and playing with a trio at a recital at Rutgers in 2013. He is every inch the distinguished, urbane professor:

As for Blues For The Viet Cong, after its brief moment in the sun in the early 1970s, it seemed to disappear from view. Entries for Stanley Cowell in some of the reference books do not even mention it. That may have been the result of a change in the political climate. The Vietnam War ended, the Viet Cong ceased to exist; Vietnam did not, as the hawks feared, tumble like a domino into the hands of some Communist monolith. Ho Chi Minh and his successors proved remarkably skillful at maintaining their country’s independence and they eventually made their peace with the capitalist west. On the other hand, events in Cambodia showed that not all self-styled Leftist liberation movements were forces for good. Nobody wrote a Blues for the Khmer Rouge.

As a title, then, Blues For The Viet Cong lost much of its meaning, shock value and perhaps its virtue. I wonder if that’s why, when the album was re-released in the late 1980s on the Black Lion label, it was re-titled Travellin’ Man after its most accomplished track?

For many years, I did not have a turntable so I had a shelf of vinyl LPs with no means of listening to them. But when I retired from work some years ago, my children clubbed together and bought me a state-of-the-art turntable. The first piece of vinyl I played on it was Blues For The Viet Cong. All those great tunes came flooding back and the album returns to that turntable again and again. The title may have dated but, to me, the music feels as fresh as ever. I would rank it as amongst my top ten favourite albums.

Stanley Cowell died in December 2020 at the age of 79. There is a sense in the obituaries that, although in many respects he had a distinguished and fulfilling career, he was still seriously underrated. Perhaps now is the time for a reappraisal of this most talented of musicians and of his masterwork, Blues For The Viet Cong.

Other pages you might find of interest :

© Sandy Brown Jazz 2021

Click HERE to join our mailing list